My first experience with Tektronix and the 545 was at Shockley Labs in about 1957. We were starting a small pilot production line for the Shockley four layer diode in the back of the Spinco Beckman building on California Avenue at Stanford. We were using HP 130 oscilloscopes on the production line but bought the 545 for use in circuit design. The scope was the envy of all the engineers.

We only had our 545 for perhaps a week when someone sent it on its cart down the steps from the second floor accidentally! I don't remember how that was resolved but shortly we had another one with several preamps and the preamp I especially loved was the dual trace.

In 1961 Shockley sent me to Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park, California for possible employment when Clevite, the new owner of Shockley Labs, laid off many employees. I joined Stanford in the Nuclear Physics Department where I helped design a calorimeter for measuring nuclear temperatures. Very shortly after joining that department I was loaned to the Geophysics Department because the SALT talks were about to shut down nuclear testing and they were short handed.

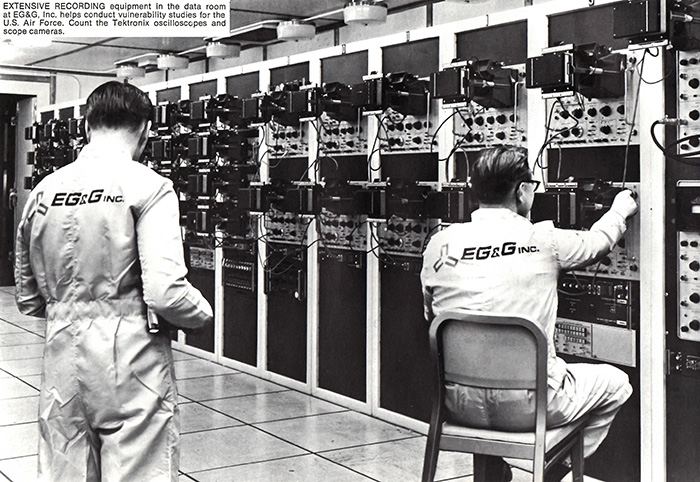

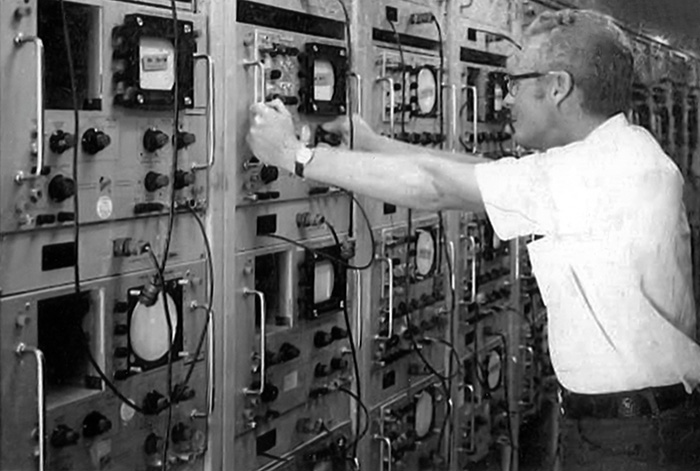

I designed and built the instrumentation vans for diagnostics at Nevada and elsewhere. The vans were 10' X 53' Fruehauf trailers and normally held 60 Tektronix oscilloscopes, some other recording equipment and three 5 ton air conditioners. The oscilloscopes were all 500 series, 545, 555, etc. In the desert heat two air conditioners were required and occasionally the third would cut in on especially hot days.

Each oscilloscope had a Beatty Coleman 4x5 camera or a high speed strip film camera with both hard film and Polaroid backs. We would dry run on Polaroid film and on shot day we change to hard film. We purchased empty preamps from Tektronix so we could build a special preamp that would allow us to send our signals directly to the vertical plates of the oscilloscopes through log compression diodes. This was an attempt to measure extremely fast rise time signals that the preamps could not handle!

We used miles of Spir-o-line from the van to the detectors. This was a huge coax about 1/2 inch in diameter. Some had solid cores and some had a spiral insulation inside the cable. The solid core was used to prevent gas from coming up the cables into the work area.

I loved these systems and operated them for ten years on numerous events for Stanford Research and E.G.&G (Edgerton, Germeshausen, and Grier, Inc. was a US defense contractor). Frequently we had to shock mount the trailers on foam blocks that would crush when the shock wave arrived. Other times we had the trailers on hydraulic mounts that absorbed the shock. Occasionally we had damaged equipment but there was a huge staff from E.G.&G that did calibration and repairs on the scopes with a fast turnaround time for the next event.

Photos copyright © David Diffenderfer. Reprinted with permission.

This photo is unrelated to David Diffenderfer and was published in the 1968 Annual Report. It shows a similar trailer installation staffed by EG&G, possibly at MIT.