What’s Up With Tek? Article

This is an excerpt from the February 2000 Oregon Business magazine article "What’s Up With Tek? The rise, fall and rebirth of Oregon's bellwether technology company" by Ted Katauskas It is an interesting look into the early history of Tektronix. Our corrections/additions are [in red].

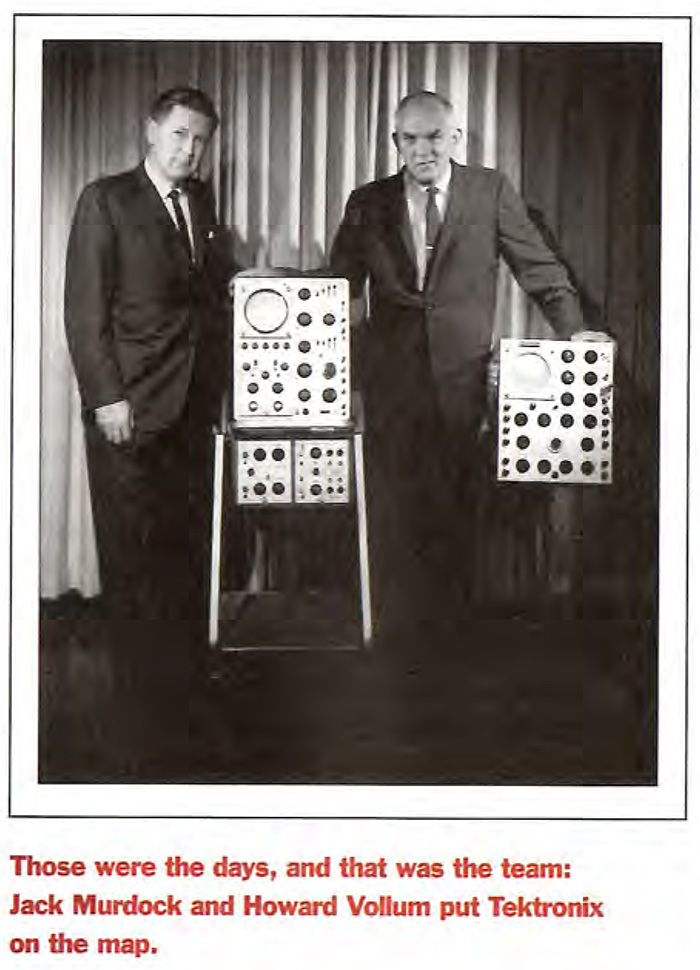

Howard Vollum and Jack Murdock never intended to build an empire. When the two friends and pre-war business associates from Southeast Portland drew up the articles of incorporation for their electronics company in December 1945. They left the document sufficiently vague, defining their enterprise as one that would "install, repair, service and sell, purchase, manufacture and otherwise acquire and deal in radio and other instruments. But it was the "other instruments" they really had in mind, specifically the cathode-ray oscilloscope.

Vollum, a brilliant, if personally reticent, young electronics engineer with a physics degree from Reed College and a Legion of Merit medal for his wartime work on radar in the Signal Corps, would be president and chief engineer. Murdock, a pre-war appliance-store owner with an engaging personality and a sharp mind for business, would be vice-president and general manager.

As head of technology, Vollum decided that Tektronix would produce a singular instrument, the oscilloscope, the eyes of the electrical engineer. Vollum knew from his radar work that commercially available oscilloscopes of the day, which had changed little since the First World War. were woefully inadequate because they offered an often-impressionistic picture of an electrical signal instead of a precise measurement of the phenomenon in question, which he was convinced the new generation of engineers truly needed.

Vollum was betting that a more sophisticated instrument would become indispensable in the development of radar, radio, television and related technologies not then invented. Still, he estimated the entire world market to be no more than 700 units.

Which suited the modest ambitions of Vollum and Murdock, who envisioned Tektronix as a small company with a familial atmosphere, and perhaps a dozen employees on its payroll.

While Murdock began buying and stockpiling all the surplus electronics the company could afford, Vollum went to work in the basement of his parents' home and created a monster called the 501. It was 18 inches tall, twice as long and twice as wide, and weighed almost as much as its creator. But it worked. Before long, Vollum had a scaled-down production prototype sitting on his bench, the 511, which was about the size of a single- drawer file cabinet, with louvered sides and a 5-inch cathode- ray-tube screen surrounded by 30 black knobs on its face. It weighed 65 pounds and was deemed portable because, unlike competing scopes, it could be hefted by a single person.

Sixteen Tektronix employees began assembling 511s in the spring of 1947 in a brand-new 6,000-square-foot building on the corner of Southeast Seventh and Hawthorne. Because the instruments were manufactured mostly from surplus parts, they could be sold at a profit for a mere $595, undercutting the competition by two-thirds. Murdock had set the price against the wishes of Vollum, who worried that not every scientist who needed a scope might be able to afford one for what to him seemed like a princely sum. [Increased to $795 by the first 511 advertisement in 1948.]

The launch of the 511 that May proved to be nothing less than a historic event. Like Tek's, oscilloscopes manufactured by Dumont, R.C.A. and Varian [we believe just Dumont and R.C.A.] let engineers see what was going on in the circuits they designed, but the 511 was the first calibrated instrument, which meant that it also let engineers measure the observed event. The CRT display was also far more sensitive and much brighter [the original CRT was an R.C.A. so likely not brighter]. The 511, which became briefly known around the world as the Vollumscope, enabled an evolutionary leap in electrical engineering; circuits could, for the first time, be designed with predictable precision.

Orders quickly outpaced production. By the end of the decade, 77 Tektronix employees were working in three eight-hour shifts, and the company was asking customers to wait six months to a year for delivery. To stimulate productivity, Vollum and Murdock instituted a profit-sharing plan, awarded in semiannual lump sums which, given the company's rapid growth, at times doubled take-home pay. "Christmas in July" became a Tek tradition, with employees buying new cars and plunking down cash deposits on starter homes. The founders also rewarded key performers with shares of their own private stock, a practice that created so many outstanding shares by the summer of 1963 that the Securities and Exchange Commission intervened and declared Tektronix to be a public company by default; TEK appeared on the big board of the New York Stock Exchange on Jan. 10, 1964.

Inside the Hawthorne plant, the industrial democracy that would permeate Tek culture for the next 40 years prevailed. Everybody was on a first-name basis, even with the chief executive, who was simply "Howard." There was no clock to punch because employees kept track of their own hours. Other than Murdock and Vollum, nobody had private offices. There were no privileged parking spaces, either; on rainy mornings Murdock and Vollum walked from their cars, sometimes from blocks away, and got soaked just like everybody else.

"Here your only status is the status you earn," Vollum would say. "and when you have that, you don't need status symbols."

It was the personality of Vollum, whose technical genius drove the company. that defined Tek's engineering culture. Because Vollum knew that some of his best ideas came to him in the middle of the night, he gave all his engineers keys to the plant and bade them come and go as they pleased.

To Vollum, the idea of advertising was almost immoral; if a product was good enough, he believed, it should be able to sell itself He backed every Tektronix instrument with a lifetime guarantee [products had a 1 year warranty but Tektronix transformers had a lifetime warranty up until 1970]. When 511s started showing up with faulty transformers after the first year of production, Vollum decided that, in the name of quality, the company should wind its own transformers, which initiated Tek's deeply ingrained tradition of vertical integration, both a blessing and a curse.

"Vertical integration wasn't always about quality, it was often about fiefdoms," observes Norm Winningstad, who worked as an engineer at the Hawthorne plant from 1950 to 1958 and left to found Tek's first successful spin-off, Floating Point Systems [Norm started as an engineer at Tektronix in 1958, pushed the idea of large screen graphic displays and left to found Floating Point Systems in 1970. Rodgers Organs was the first Tektronix successful spin-off]. “Everybody controlled their own little fief, and nobody could order components from outside the company - even when other suppliers could make them just as well as Tek could, and far more cheaply."

But vertical integration also fostered risk-taking and innovation.

In 1951. when Tek engineers reported that the capabilities of commercially available cathode-ray tubes at the heart of every Tek oscilloscope -were the main obstacle to advancing the performance of the instrument, they decided, with Vollum's blessing. to make ones that would meet their rigid specifications - an expensive undertaking that many industry experts deemed foolhardy, if not impossible. After four years of repeated setbacks, Tek triumphed producing the world's finest CRTs. [the CRT effort was started in 1951 and the first oscilloscopes using this CRT were produced in 1954, just 3 years later].

"It was just exciting," recalls Les Stevens, who arrived at Tek as an accountant in 1950 and eventually became the company's chief financial officer [Les was VP of Finance, but we have no records of him as CFO]. "We were good and we knew we were good. We were winning and we couldn't be beat."

Tek soon controlled nearly 80% of the world oscilloscope market and continued to grow exponentially.

From 1949 to 1951. sales quadrupled to $4 million, as did the payroll, which swelled to more than 300. The company moved from its cramped quarters in Southeast Portland to a 20,000- square-foot factory on four acres between Southwest Barnes Road and the Sunset Highway. By 1959, with sales approaching $32 million and a workforce of nearly 3,000, Tek had outgrown even the Sunset Plant and had begun moving to a new 313-acre campus that was being built on a former dairy farm in Beaverton [we have no records of this being a dairy farm but was mostly described as swamp].

Murdock by this time had, for all practical purposes. left Tek to pursue other business interests and his passion for flying; and Vollum, who had relinquished his duties as chief engineer. began sharing the responsibilities of what he liked to call the "administrative folderol" with a new executive vice-president.

Rather than recruiting a team of Ivy League experts to help him run Tektronix, Vollum hand-picked his own managers from within the company. Almost none had any formal schooling in business. But neither did Vollum, who led largely by quiet example. He often ate lunch with assembly line workers and machinists in the cafeteria. He walked from bench to bench and immersed himself in the details of every project, once lingering there until the phone rang and an irritated board member summoned him to a director's meeting. He personally signed and sent Christmas and birthday cards to every Tek employee until 1970, when the ranks swelled to nearly 10,000.

"Howard Vollum hated the day that Tektronix got to be so big that he couldn't remember everybody's name;” says Larry Mayhew, who from 1970 to 1981 managed Tek's Information Display Division, the company's premature and ultimately abortive foray into the computer world. "He had such tremendous affection for what he had created that he didn't want it to change."

But everything seemed to change all at once in 1971. On May 16, Jack Murdock, Vollum's longtime friend and associate, died after his floatplane crashed into the Columbia River. Later that same month, Vollum suffered a heart attack. Then in August, on the day Tek released its annual report with the dismal news that sales had fallen by 12 percent and earnings had plummeted by nearly 35 percent, executive vice-president Earl Wantland announced that Tektronix would be laying off 350 employees. It was company's the first cutback ever.

Tektronix quickly recovered, but by the time Vollum handed the presidency over to Wantland in 1972, a rift had opened among the company's management - those like Mayhew who saw a need for Tektronix to invest heavily in the emerging and unknown market of computers, and others who followed Vollum's lead and believed Tek should cautiously stick to the business it knew best and dominated: oscilloscopes.

Wantland found himself trapped between both sides.

"I don't know how much you know about taking over a company from its founder, but the world has a special graveyard for folks who have done that," says Wantland, who notes that Vollum continued to exert a strong influence over all key decisions after he left office. "You can't ignore somebody who has been bigger than life for the entire history of the company. Howard usually had awfully good judgment- but he just had a blind spot about where computers were going and that retarded our progress for sure."

In the early 1970s, Wantland, with lukewarm support from Vollum, gave Mayhew everything he needed, including a new 250,000 square-foot factory in Wilsonville that is now owned by Xerox, to produce a device that many Tek old-timers consider to be the world's first desktop computer, the 4051.

The 4051 was a graphics computer built around a proprietary Tektronix cathode-ray storage tube, which worked much like an Etch-A-Sketch, using an electron beam to draw an image on a layer of phosphorus [phosphor] on the screen of the CRT. Because the image, after being written just once, was locked in the screen's phosphor until it was erased, the 4051 required little in the way of computer memory, which was prohibitively expensive at the time. Graphics workstations of the day used TV-like raster tubes, which required continuous rewriting of the image while it was being viewed, an enormous demand on computer memory, so much that the machines needed the assistance of refrigerator-sized mainframe computers. The little 4051 could do the processing job all on its own.

Tek launched the 4051 late in 1975, at about the same time IBM unveiled its 5100, the 50-pound precursor to the revolutionary PC. IBM's nascent desktop computer, which displayed text on a wallet-sized monochrome screen, was a flop while the 4051 quickly became Tek's best-selling product. It could process numerical data and display graphs and circuit diagrams on a 48-square-inch monochrome screen that could be viewed without distortion from eight feet away. Within two years, Mayhew's little Wilsonville computer business accounted for nearly a quarter of Tek's sales.

"We made a lot of money off of the 4051. but we never went as far with it as we should have,'' says Mayhew. "It's like we traveled from Portland to Gresham instead of to Paris. It was just silly."

The 4051's most critical flaw was that it was simply ahead of its time. Tektronix had no comprehensive and user-friendly applications software package to sell with it; imagine buying a computer with virtually nothing on it but BASIC, the new computer language that Microsoft had written only that year. The proud new owner of a 4051 who wasn't conversant with BASIC had to hire a computer programmer to get the machine to do whatever it was needed to do. Mayhew says he nearly convinced the Tek hierarchy to buy a computer-aided-design business with a comprehensive suite of easy-to-use software, but the deal ultimately was voted down.

"I remember this like it was yesterday" says Gerry Langeler, who helped Mayhew arrange the acquisition before he left Tek in 1981 to start Mentor Graphics, which quickly took over the graphics workstation market. "The head of R&D stood up and said "software is not technology." That was the day that I sort of realized that Tek was going to fail, because if the company at its core felt that software was not technology, then it didn't understand the new computing age.

The 4051 and its proprietary Etch-A-Sketch tube became a historical footnote by the early 1980s, when the rapidly falling cost of memory enabled companies like IBM co produce superior machines with raster monitors. Unlike the Tek storage tube, these raster-scan CRTs could produce color images, a huge advantage. Throughout the decade, Tek tried again and again to re-enter the computer market with state-of-the art products, but the company had fallen too far behind the competition and because of its on-again-off-again approach to the market, eventually failed to attract third-party software developers.

By the time of Vollum's death in 1986, Tektronix had already begun its downward spiral, while rivals that had successfully redefined themselves as computer companies continued to flourish - like Hewlett-Packard, a test-and-measurement business incorporated a year after Tek that today is a $42 billion company employing more than 83,000.

"Let me tell you, there were no simple issues, they only sound simple one by one," says Bill Walker, a current Tek board member who was the company's chief engineer from 1968 to 1983. "Yes, we missed huge opportunities in the desktop computer market, huge opportunities. It came about because of the way we were structured, more or Jess around the fact that oscilloscopes had been our business for so long and we had been so successful that it became very difficult for us to do anything else."