Howard Vollum was drafted before the United States entered World War Two and was sent to Camp Roberts, located about halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco. He described it as the "middle of nowhere". His group was the first to occupy the site and in the first few days the arriving draftees were arbitrarily divided in two, with one group sent to the infantry, the other the artillery. Howard landed in the infantry; it was a completely random selection process.

Howard spent three months of basic training at Camp Roberts, at the end of which his fellow recruits were sent off overseas. Many of these draftees were sent to the Pacific where Howard later learned they had "some pretty rough times" once the war started. Howard didn't get shipped out because he had met an officer from Milwaukie, Oregon, who was an engineer with the Bonneville Power Administration. The officer got to know Howard and took advantage of his expertise by having Howard fix radios on the base. Howard's electronics skills were highly prized and he remained on the base for the arrival of the next ninety day group.

Howard later applied for officer's candidate school as well as a program initiated by the British to have Americans come to England for six months to train on their radar systems, at the time the best in the world. There was also a third option where American soldiers with physics or engineering degrees could qualify for an Electronics Training Group that President Roosevelt had initiated. Howard had received his Bachelor's Degree in physics from Reed College in Portland. All these programs were of interest to Howard, but he became frustrated when nothing happened for several months after he had applied.

The situation changed dramatically on December 7, 1941, the day the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Within a few days Howard was promoted from Corporal to Second Lieutenant. This happened so rapidly even the camp commander wasn't notified. Howard had previously been interviewed at one point by what he identified as "some traveling Washington guys" and they apparently singled Howard out for special treatment. Not long thereafter, Howard was reassigned to Fort Monmouth in New Jersey and was immediately transferred without an opportunity to return home to Portland. He just boarded a train and went directly to the East Coast.

Fort Monmouth was headquarters for the Army Signal Corps and at the time was a collection point for hand-picked recruits newly bound for the radar training program in England. Howard remained in New Jersey until the entire designated group was assembled and then traveled to Halifax, Nova Scotia by train to make the voyage across the Atlantic. There was a week's delay in Halifax because they had a little problem with some "sinkings", presumably by German submarines. Howard noted that a prior group had "gotten a little bit wet", but were ready to try a second time. Howard boarded a Dutch passenger liner appropriately named the Volendam and they made the trip with a partial destroyer escort without incident.

In a suburb of London Howard started what was to be a three month training course followed by three months of hands-on work. Several types of radar existed at the time and Howard was trained on his preference, a high frequency system (200 to 250 MHz) used with searchlights to track and illuminate aircraft so they could be targeted by antiaircraft guns. Howard and another American finished at the top of the class and were promoted to First Lieutenant.

The standard outcome of this training for Americans was a return trip home, but Howard elected to stay in England. He was sent to Christchurch on the coast and where he joined a group developing a newer radar system. He never actually worked further on the searchlight radar he had been trained on. The objective of the newer program was to implement a radar fire control system to direct 15 inch guns on German shipping in the English Channel at Dover. This program was given a very high priority and Howard's role was to develop the display, or so-called indicator unit, for the system, which appropriately enough, was a specific type of oscilloscope.

The standard procedure for an American working in the signal corps in England was to rotate out of an assignment after three months. Howard received repeated extensions of service and remained in the coastal radar display development program for over two years, operating under a top security clearance. It was probably the highest performing radar system at the time, employing high power, 0.1 microsecond pulses.

During this time Howard routinely used Crosier oscilloscopes, the leading British brand analogous to DuMont in the US at the time. But the Crosier units weren't suited for the high frequency work Howard was doing so he was forced to create his own custom modifications in so-called bench "lash ups" without cabinets. He worked closely with British radar experts from Oxford and Cambridge. Howard spent a total of two and half years in England.

Upon his return to the USA, he was stationed at Camp Evans in New Jersey.

At Camp Evans Howard went to work on another fire control system, this one capable of tracking mortar shells with radar that in turn could respond to remove the threat. Mortars were significant weapons in WW2 - more soldiers were killed with mortars than machine guns. Howard's work involved tracking the parabolic path of the mortar shell and extrapolating back to its source.

In addition to the effort at Camp Evans, the Army also had a group at MIT working on anti-mortar radar and Howard spend a great deal of time going back and forth between the Signal Corp Labs in New Jersey and Boston. He made so many trips he got to know the porters by their first names.

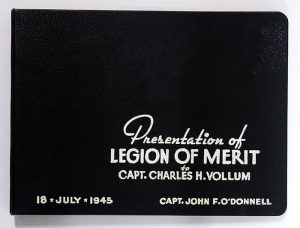

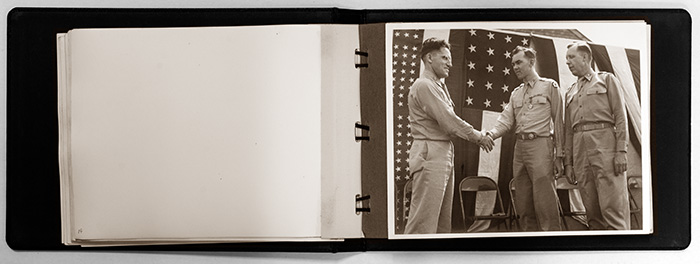

On July 18, 1945 during his time at Camp Evans, Howard was awarded the Legion of Merit for his work in England. Howard eventually attained the rank of Captain and was discharged in November, 1945. His efforts at Camp Evans resulted in Howard later receiving a second Legion of Merit Award in the form of an Oak Leaf Cluster.

It was extraordinary for an officer of the rank of Captain to receive the Legion of Merit award. Past recipients have predominantly been heads of state and general officers or colonels.

This July 26, 1945 issue of the Camp Evans newsletter Signaleer features Howard receiving the Legion of Merit award - the last paragraph is quite descriptive. Click on the image to view the PDF.

This July 29, 1945 Oregonian article describes Howard being awarded his Legion of Merit.

Two days after World War Two ended, the New York Daily News published an article on the long-secret story of radar, describing it as "second only to the atomic bomb as the war's most revolutionary scientific development, the margin of victory in the Allies' darkest hours and a springboard to the perfection of television and the other far reaching changes in postwar living."

The vintageTEK museum obtained photo album that was assembled by Captain John F. O'Donnell, a colleague of Howard Vollum at Camp Evans, from Howard's award ceremony. Captain O'Donnell was later a successful businessman and real estate developer in Portland whose family was associated with the Union Meat Company and the Lipman-Wolfe Companies. The individual from whom the museum acquired the album learned that Howard had asked Mr. O'Donnell if he would invest in Tektronix in late 1946, but O'Donnell felt the idea was too risky and he declined.

The InfoAge Science & History Center is the steward of 16 buildings on the historic Camp Evans campus. Then have signage displaying the history of Howard Vollum at Camp Evans and his legacy of Tektronix. There is also a video of the dedication of this display on our Video Gallery.

The photo album we obtained contained other photos of camp personnel which shared with InfoAge Science and History Center. In return they sent us a scan of the above article from the Signaleer in their archives.

This biography of Howard is an extract from the "History and Environment Of Tektronix" document, a 249 page document published in October of 1978 and was edited by Robert Bosler.

Charles Howard Vollum

Charles Howard Vollum was born on May 31, 1913 in Portland, Oregon. He graduated from St. Agatha's School and St. Stephens (now Central High School), and he attended Columbia University (now the University of Portland)for two years.

Legend has it that he built his first oscilloscope while at Columbia University. An early acquaintance, Frank Hood, remembers one of those early instruments as looking like a "breadbox crammed with parts with a piece of sewer pipe on top" (the sewer pipe was to shield the display from the earth's magnetic field.

Legend also has it that Howard tried to transfer to Oregon State but was turned down for lack of credentials; he then took his oscilloscope over to Reed College where he was accepted.

Reed College at the time had some extraordinary educators in its physics department, including Dr. Marcus O'Day and Dr. A. A. Knowlton. Dr. Knowlton particularly was noted for the quality of students he trained which resulted in Reed College ranking ahead of colleges such as Stanford in numbers of graduates listed in American Men Of Science during the 1930's. Dr. Knowlton published a textbook in 1928 which revolutionized college physics instruction by approaching physics from a humanistic rather than purely technical standpoint. Dr. Knowlton was also noted for his fierce and lifelong espousal of academic freedom. He taught at Reed College for 33 years. Dr. Knowlton consulted for industry and found, for example, a method for solving the problem of static electricity blotting out airplane radio reception.

Howard's senior thesis in physics at Reed was "A Stable Beat Frequency Oscillator Equipped with a Direct Reading Frequency Meter". The thesis reflected Howard's determination to design instruments that would, as Frank Hood remembers that Howard said many times during this period, "produce not qualitative readings, but quantitative readings." In fact, the instrument that Howard built and described in his thesis offered an accuracy in measuring frequency of 1 percent at a time when conventional designs could measure to only 10 percent. Howard also built an oscilloscope at Reed that was still in regular use 22 years later (on the 10th anniversary of Tektronix)

After graduating from Reed in 1936, Howard worked on his own for a while repairing electrical appliances, then joined the M. J. Murdock Company. Howard worked at servicing and installing home and auto radios and air conditioning devices for four years until, in 1940, he placed first in a competitive exam and for $150 a month supervised the Radio Project of the National Youth Administration, a defense project to teach young people the basics of electronics.

At the age of 26, Howard Vollum was drafted. He would later say that it was “the only lottery I ever won”. On March 4, 1940, his military career started with infantry training at Camp Roberts, where he stayed for nine months. Legend has it that during this period the Camp General’s radio broke down, and Howard fixed it with ease. In any case, Howard received the first direct commission ever given at Camp Roberts and was transferred into the Signal Corps and was assigned to the Electronics Training Group.

At the time, the custom was for members of the Electronics Training Group to be sent to England for a period of eight months duty as radar maintenance officers since British radar technology was foremost in the world. Instead of radar maintenance, Howard was sent to the English radar laboratory, the Air Defense Research and Development Establishment. The January 10, 1956, issue of Tek Talk describes that assignment as follows: “There he worked for almost two and one half years as a development engineer on a high resolution radar for aiming the 15-inch Coast Artillery guns at Dover. This radar was easily the most accurate in service at that time, having a range error of three yards at 20,000 yards (about 11 miles) and azimuth or angular error of 1/20 of a degree. This radar was very effective in aiming guns which sank German ships trying to sneak out of the English Channel at night. For this work, Howard was awarded the Legion of Merit Medal.”

“On his return to the USA just a few days before ‘D Day’, he was assigned to the Evans Signal Laboratory at Belmar, New Jersey. There he worked on radar detection and location of enemy mortars. This is accomplished by observing the flight of the shells and using this data to compute the location of the mortar. The same radar-computer combination is used for laying our own mortar fire on enemy mortar positions. For this work, he was given an Oak Leaf Cluster indicating a second award of the Legion of Merit Medal.”

While at the Evans Signal Lab, Howard met Bill Hewlett, who was stationed at a nearby Signal Corps lab in Washington, D.C. Bill Webber, who knew Howard at the time, remembers Bill Hewlett saying years later, “our biggest mistake was not hiring Howard Vollum. I wrote Dave Packard telling him to hire Howard, but he never did it ....”

In any case, after the war, Howard Vollum decided not to move to Palo Alto, California, where the electronics industry was starting to form. Instead, in late 1945, Howard returned to Portland.