Tektronix Enters The Graphics Business

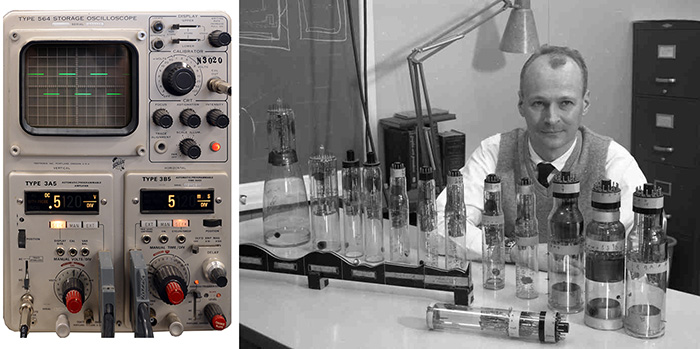

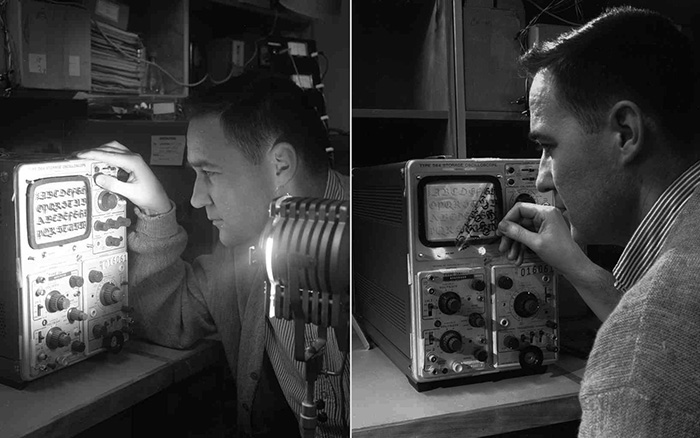

The heart of the 564 storage oscilloscope and enabling technology for Tek’s computer graphics business was found in a special cathode-ray tube (CRT) conceived and developed by Bob Anderson. He started at Tek in 1960, working in the Future Products research group for Dick Ropiequet. Bob had worked at Hughes Aircraft on their Memotron storage CRT and was convinced he could come up with a simpler, less expensive design that could store an oscilloscope trace on a CRT screen without the need for refresh. Within a year, he demonstrated a meshless storage tube called the Direct View Storage Tube (DVST) that was incorporated in the 10MHz 564 storage scope, introduced in June 1962. If that were the end of the story, it would still be a milestone in Tektronix’s history, initiating a long product line of analog storage scopes. But there was to be much more.

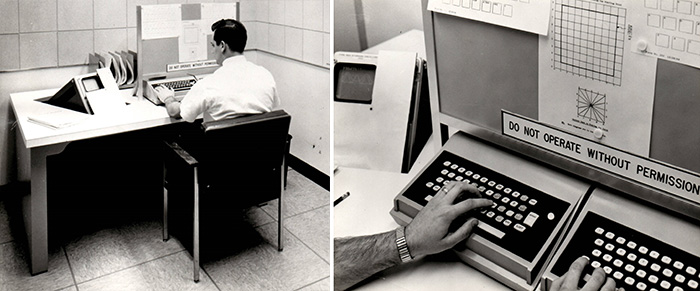

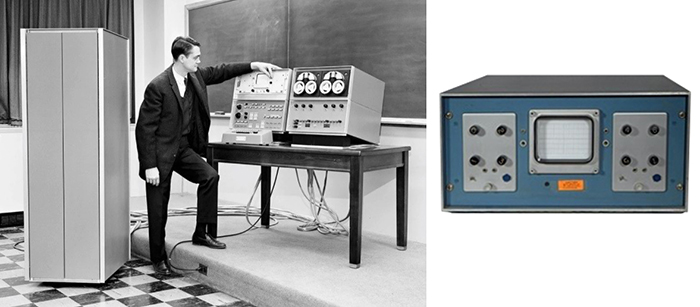

Sometime after the 564’s introduction, Tek Field Engineers reported back to Beaverton that they had a seen a very peculiar use for the 564, and they had the photos to back them up. Computer programmers at the defense contractor, the TRW Corporation in Southern California, were using 564s mounted in a desktop with the controls blocked by a panel–only the display was visible. They were using the 564 as part of a computer terminal!

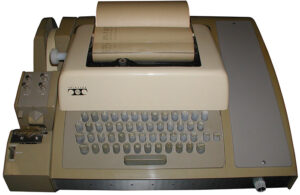

Professor Glenn Culler of the University of California, Santa Barbara, was a mathematician who wanted to make use of computers in an interactive manner to teach his students to do computational, predictive modeling on physics problems, for example, to characterize plasma discharges. Most mainframe computers of the time operated in a batch processing mode that didn’t permit this sort of interactivity. Limited dynamic computer memory, typically measured in kilobytes, dampened use of conventional CRT displays because they required precious memory to refresh the screen content. At this time a typical amount of accessible computer memory was measured in single-digit kilobytes. The primary computer interface at the time was the teletypewriter, with the primary vendor providing the generic nickname: Teletype. However, a Teletype machine was limited to printing alphanumerics; detailed graphics, plots and realistic images were beyond its capability. And in addition to having a slow response, the impact printers were also quite noisy.

At some point after learning of the Tek 564 Dr. Culler had a “eureka” moment, realizing the screen storage function on the new scope could enable a dramatic improvement in computer interactivity without sacrificing computer memory. This was in spite of the scope’s tiny 5-inch diagonal screen and the fact they were using an entire oscilloscope despite only employing the storage CRT. The photos Tek obtained in 1965 from TRW, where Dr. Culler was consulting, show his idea reduced to practice. Computer users were blocked from making any adjustments to the instrument.

Professor Culler and a colleague made presentations at academic conferences and published a paper describing the computer lab they created using the Tek DVST as a terminal. At some point prior to 1964, Prof. Culler made contact with Norman Winningstad, an engineering manager at Tektronix, likely requesting that Tektronix design a computer terminal product. However, Tektronix did not respond, so in frustration Dr. Culler pursued this on his own, convincing a Massachusetts-based computer company called BBN (Bolt Beranek and Newman) to produce a terminal he named the “Teleputer”. Introduced in 1965, it employed the 564 CRT and drive circuitry.

While clearly not acting fast enough for Dr. Culler’s liking, Norm Winningstad began collecting information to make a case for Tektronix’s entry into the computer terminal market. Meanwhile researchers at Tek had discovered other intriguing things a DVST could do:

- An image stored on a DVST screen could be recorded electrically and transmitted in a serial fashion over a phone line to either a conventional CRT or a DVST. This was potentially much simpler than any other means of screenshot transmission known at the time.

- Tek engineer John Mepham discovered an image projected onto the screen of a DVST with a bright light could be stored on the screen as though it had been written by the electron gun. This image could also be transmitted as described in the prior paragraph. At the time commercial electronic facsimile was in its infancy.

Norm Winningstad pursued these developments, but they complicated the computer graphics business proposal. It was eventually determined that given the limitations of the relatively slow phone transmission rates at the time, sending screen data from DVSTs was too costly. And the optical storage opportunity was still very much in a proof-of-concept mode.

Norm Winningstad decided to only bring computer graphics display opportunity to senior management for consideration. In late 1964 he distributed a memo and made a presentation proposing that Tek enter fledgling computer graphics display market. The reviewing committee was headed by Tektronix President, Howard Vollum, who had well-defined prerequisite regarding new business opportunities. He required that a new business venture offer a profit margin at least as good as that of the oscilloscope business. He also only would consider entering a new business where Tek would have a commanding presence, protected either by patents or some other technology barrier.

Norm Winningstad reported that his proposal met both requirements, the committee agreed and his proposal was approved. Design work started for two new DVST CRTs optimized for use in computer graphics terminals, along with the appropriate drive circuitry. The new business unit focused on computer graphics displays was revealed to employees in Tek Week in the September 24, 1965 issue. This was one of the first new Tektronix ventures not involving electronics test and measurement.

Part of what convinced Norm Winningstad of the potential market size for the opportunity was a massive government program called Project MAC that had been launched at MIT in 1963. The US military had been alarmed by their recent poor performance of their worldwide command and control network during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Since the late 1950s the Pentagon had been in the process of widely employing computers to manage data and communications throughout the vast Cold War early warning facilities and defensive assets, but during the October 1962 showdown between the Soviet Union and the United States there had been troubling breakdowns that severely handicapped responses within the system. Inefficiencies in the so called ‘man-machine interface’ were determined to be a key shortcoming. Project MAC, managed by MIT, was created to address this problem. There were projections for a dramatic increase in the number of seats for both military and civilian computer users from the project. Norm Winningstad envisioned a large number of these could potentially employ Tek terminals because of the increased efficiency of using a DVST.

MIT had been a pioneer in the development of computers and a new, much smaller computer had just been demonstrated. Called the LINC, for Laboratory INstrument Computer, the computer consisted of a cabinet about the size of a household refrigerator that contained memory and power supplies, and four smaller modules, used for control and interfacing. One of the modules made use of a modified rack mount Tektronix 561 oscilloscope that served as the computer terminal. Knobs on the plugins were used for X/Y cursor control, effectively served the function of a mouse. The LINC computer was one of the first to employ an integrated display.

Independent of Norm Winningstad’s input it’s likely MIT engineers from Project MAC learned of Professor Culler’s use of Tek storage tubes as computer terminals from his public lectures and/or publications. In 1967 MIT engineers Richard Stotz and Tom Cheek presented an academic paper outlining their design for a new terminal that would employ Tek’s DVST. They later formed a company call Computer Displays, Inc. to implement their design.

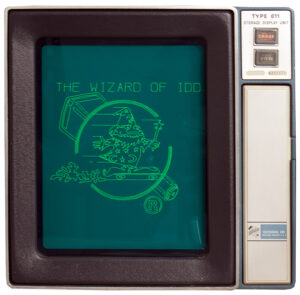

Tektronix’s CRT design engineers created two DVST designs optimized for use as computer displays: one was the T601, a 5-inch diagonal tube intended to replace the products where the T564 CRT had been used. The other offering was the groundbreaking T611 DVST, a large-screen (for the time) display tube with a flat-face and capability of displaying roughly 800x600 pixel resolution.

By the mid-1960s Tektronix’s CRT group had been in existence only slightly more than ten years. They had surmounted significant challenges in designing and manufacturing an impressive array of high-performance oscilloscope CRTs. But these new tubes provided new obstacles. The specialized phosphor screen used in the 564 performed well for storing oscilloscope traces, but there were higher-level demands for storing alphanumerics. For example, there was a need to resolve the open spaces in a lower-case “e” or in the number “8” and the T564 screen structure was not up to the task. A new process and screen design was needed. The ceramics group had only been producing CRT funnels for a few years when they were called upon to design and manufacture a funnel for the 11-inch DVST which was the larger ceramic funnel they ever produced. There were also new aspects of writing and flood gun design for the larger tubes that also charted unknown territory. Development of an optimized storage screen design and process took several iterations.

Tektronix announced the availability of the 611 display module in October 1967 for $2500.

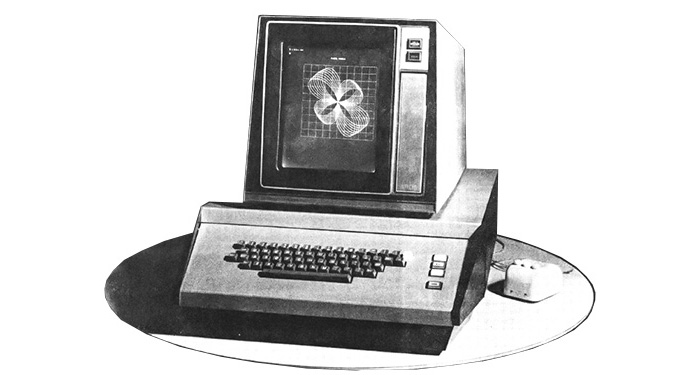

Lacking a character generator and a keyboard, this was not a fully functional terminal, but it was used by Stotz and Cheek in their company’s computer terminal design called ARDS (Advanced Remote Display Station) introduced in February 1968. The company was later dissolved and Tom Cheek came to work at Tektronix.

The ARDS terminal from Computer Displays Inc. employing a Tektronix 611

Photo courtesy of Github PDP10 #821

VintageTek museum volunteer, John Ollis, used an ARDS terminal when he was in college and shared this story.

| I worked for three years at the engineering departments computer center while going to University, first as a computer operator than as a hardware technician. We had an ARDS connected to a Scientific Engineering Laboratories (SEL) 810B minicomputer through an in house built serial interface. I was responsible for maintaining that section of the computer center.

I have always thought the ARDS baud rate was limited 1200 baud because the spec they had for the 611 was the time it took to store a dot, rather than how quickly you could write a stored vector. My understanding is that they used a Bresenham algorithm based vector generator. My recollection is that I got that information from Tom Cheek who was connected to the project. Old memories get fuzzy. The ARDS used some sort of variable (RC?) oscillator for the baud rate generator. At first, our interface also used a rather crufty TTL inverter based RC oscillator. Yes, not a good choice. I would have to periodically adjust the ARDS baud rate. I would key in a short memorized program to the SEL that would continuously send out A's. Then, remove the ARDS keyboard to get at the electronics tucked under the 611 and tweak the baud rate pot low until failure, high until failure and then leave it centered between the two. Eventually, our interface was redesigned and the RC oscillator was replaced with a crystal. Things worked a lot better then. I also, repaired the 611 twice. First by cleaning the 611 fan's filter, which probably just postponed the second fix, which was replacing a power transistor. The ARDS was a really fun toy. It was where Instant Art began. I even wrote a version of Conway's Life for it, which really ran slowly. At the same center, I also got some experience with the 4501 Scan Converter. I sent it a bunch of Instant Art images, video taped the output and displayed it at the annual Engineering Week at the University. Maybe, my experience with the ARDS and the 4501 Scan Converter helped get me hired at IDG. I know that working at that computer center made me much better prepared to face the real world. |

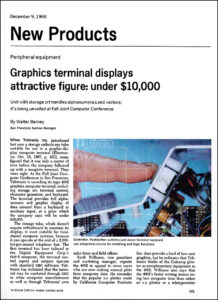

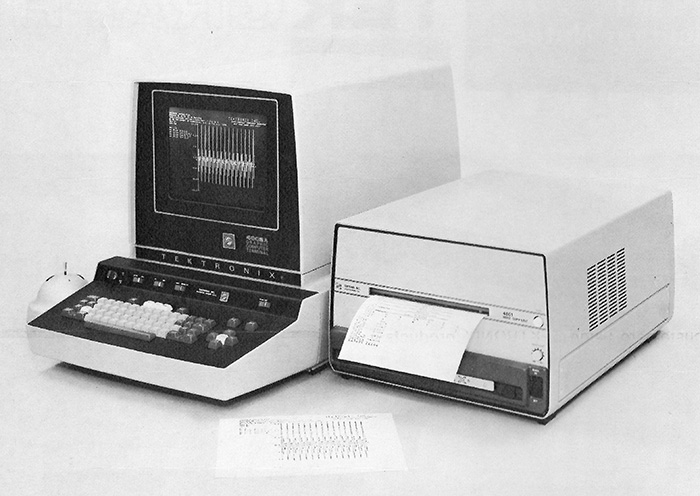

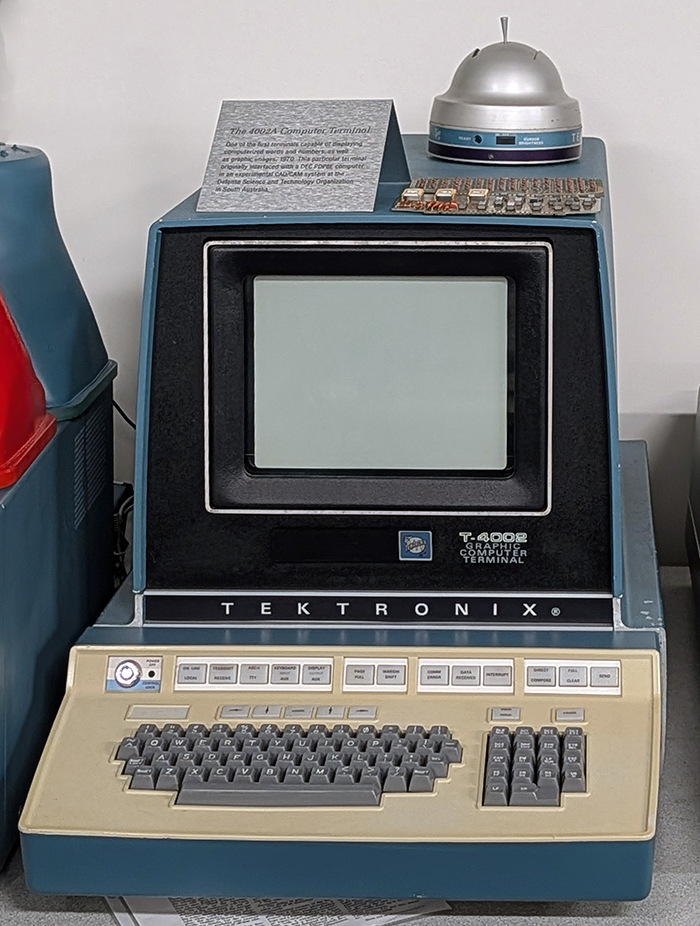

In December of 1968 Tektronix announced its own computer terminal design, the T4002, and proceeded to dominate the computer terminal market, employing the company’s proprietary DVST technology. The terminal was sold for $8,800. At the time an IBM terminal employing a conventional CRT and dedicated memory was sold for $80k and more, depending on options.

This December 9, 1968 article in Electronics describes the T4002 terminal. Click on the image to view the PDF.

The remarkable ability of Tektronix DVST terminals to render complex line drawings and detailed graphs of data was much appreciated by customers. But almost immediately there was an outcry for the ability to incorporate these images into written reports. Initially the best solution was to use photography, but even with Polaroid’s fast-developing film, the result was not satisfying. This problem was resolved with the introduction of 4601 hard copy unit. Tektronix designed a new CRT incorporating collimating, fiber optic faceplate to make use of 3M’s Dry Silver photosensitive paper.

The museum has this T4002 on display. The front keyboard bezel is hand-made in the model shop so we believe this is an original T4002 prototype that was reused for the T4002A development. The "A" revision replaced a number of diode memory boards used for the character matrix with a ROM.

The DVST enabled Tektronix to dominate the computer graphics display market with a series of groundbreaking products. For more information see our DVST Graphic Terminals page.